S Westlake - 1, S Stacey - 1, M Beagle - 1, M Aliprantis - 2

1 - Greater Wellington Regional Council, Wellington, NEW ZEALAND

2 - Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment, Wellington, NEW ZEALAND

Abstract

Regional Councils in New Zealand have joined together to help the country’s climate resilience and Covid 19 economic recovery. Kānoa, (within the New Zealand Governments’ Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment) has provided $211M government funding to assist with programmes of work for 55 projects at 14 different councils, along with $134M from Regional Councils, making a total programme value of $354M. Government priorities for these projects are climate resilience and social procurement; regional council project priorities include accelerating work programmes for flood risk management, and demonstrating that councils can deliver projects supported by government’s financial contribution.

Greater Wellington Regional Council (GW) is part of this initiative and is delivering a programme of work at 15 different sites in 3 catchments over 2 years, with budget value $22.7M. To align the programme aspirations of government and council, GW project delivery has shifted to a ‘new reality’. This includes building partnerships with Māori, putting co-design collaborative relationships in place and a greater emphasis on social and sustainable procurement.

This paper discusses how we have worked with these shifting values, taking new approaches for these projects alongside ‘business as usual’, as well as the challenges, results and lessons learned.

Flooding in New Zealand

New Zealand now faces, on average, one major flood event every eight months (Te Uru Kahika, 2022), with flood protection schemes as the first line of defence. These schemes provide protection to around 1.5 million hectares of New Zealand’s most intensely populated and farmed land. They also provide safety, security and protection to the families, marae, livelihoods, and communities living alongside rivers in over 100 towns and cities.

To meet performance standards under conditions of more frequent and intense climate change-induced flood events, these flood protection schemes require ongoing substantial upgrades, renewal and management. The schemes are also required to meet many more community, environmental, cultural and economic objectives than in the past, including climate adaptation and improved water quality requirements. The maintenance and improvement of flood protection across New Zealand has a clear national interest and many assets, including government assets, receive substantial benefits from rate funded flood protection. This results in a national inequity as many government assets are protected by flood protection schemes, however government does not contribute to their funding.

To meet the ongoing funding requirements for flood schemes, the River Managers Special Interest Group (a group of Regional Council Flood Risk Managers), has sought on-going co-investment from government in river management. Government is still considering this request in the context of the wider flood risk management considerations including non-structural options such as managed retreat. The Kānoa funding package is considered a first step in demonstrating an effective partnership for ongoing government co-investment for the upgrading of flood risk management schemes to meet the wider Government objectives.

Kānoa

Kānoa - Regional Economic Development and Investment Unit (Kānoa) (formerly known as the Provincial Development Unit) was established in 2018 within the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) to support delivery of government funding to enhance economic development opportunities in regional New Zealand. Kānoa works with other Government organisations and industry, communities, iwi (Māori tribes) and local government to manage and deliver funds tailored to build regional economies.

Wanting to boost economic and social development in areas adversely affected by Covid-19 lockdowns, Kānoa sought ‘shovel ready’ infrastructure projects that could be considered as part of a stimulatory package to support regional businesses such as the construction industry. Projects supported by Kānoa are subject to a funding agreement with two broad outcomes:

- Engineering outcomes – Building infrastructure to protect communities against flood damage and the impacts of climate change.

- Social Procurement Outcomes – Inclusion of environmental enhancements and societal improvement alongside delivery of engineering outcomes.

Social Procurement outcomes include promotion of the use of local businesses, supplier diversity including owned/operated Māori and Pasifika businesses and organisations and targeting female and youth employment.

As Kānoa was seeking to provide funding support to substantive projects, Regional Councils from throughout New Zealand joined together and assembled a single package of 55 river management and flood protection projects at 14 different councils. Kānoa, has provided $211M government funding for the work, and $134M is co-funded by Regional Councils, giving a total programme value of $354M. These projects provide climate resilience for towns, communities and businesses through flood protection and help accelerate New Zealand’s recovery from Covid-19 through employment opportunities.

Within this package of work, GW has secured funding for two projects located in the Wellington Region.

Greater Wellington Regional Council

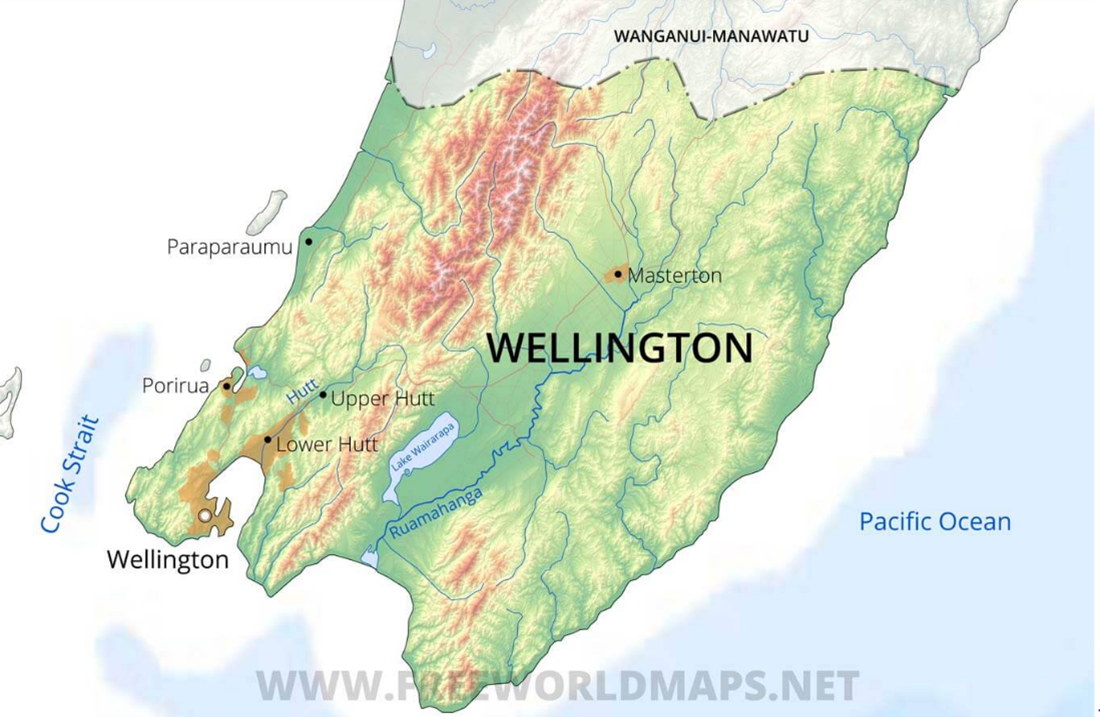

The Greater Wellington region covers the lower North Island of New Zealand (as shown in Figure 1) and has a population of 506,814 (Stats NZ, 2018) and a land area of 8,130 square kilometres (GW, 2022). Within the region, development has historically concentrated on the floodplains of river and streams as these are generally flat and fertile. However, development has also often been placed too close to the watercourses leaving them no room to move naturally, or with space for their floodwater, which has resulted in increased impact of flood events. The Greater Wellington Regional Council (GW) has a responsibility for flood risk management within the Wellington Region of New Zealand (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Wellington Region

Flood Risk Management

GW has the mandate to protect communities within the region from flooding using the most appropriate methods under the Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941 (GW Flood Protection Department, 2013) The Act is enabling, meaning GW can carry out physical works (including structural measures) to mitigate erosion damage and protect property from flooding, but is not required to do so. However, GW is required to maintain in good repair the works that it has chosen to carry out. In the Wellington Region, only rivers and larger streams of “regional significance” are managed by GW. City and district councils handle smaller urban streams and stormwater channels. In effect, this means that it is up to GW and the local community to determine those rivers requiring most attention and the nature of the works required. In some areas, GW or its predecessors has chosen to undertake flood protection capital works, and GW then takes responsibility for maintaining and where appropriate improving these works.

The Floodplain Management Planning framework is used by GW and communities to evaluate and decide on application of techniques to manage flood risk. GW uses four main flood risk management techniques, as described below.

- Planning controls – Managing flood risk by providing advice on flood risk for development and working with Territorial Authorities (TAs) (City Councils) to control development in flood hazard areas through District Planning rules. Flood hazard mapping, to identify areas subject to flood hazard is the responsibility of both GW and TAs under the Resource Management Act. Since this legislation was passed, each authority has prioritised and undertaken flood hazard mapping of the catchments that fall under its jurisdiction.

- River management – Reduction of risk through channel maintenance and keeping watercourses clear to allow flood flow conveyance.

- Engineering controls – Risk management through the construction of engineering flood defences such as stop banks or through allowing the river more room. Noting that these measures only manage the flood hazard up to the design flood standard and the residual flood hazard remains.

- Flood Warning & Response – Managing the risk, particularly the residual risk, through emergency readiness, response, and recovery procedures. This is carried out in combination with Emergency Management providers.

Within the Wellington Region, GW has 15 Schemes it is responsible for using this Floodplain Management Planning framework.

Greater Wellington Projects

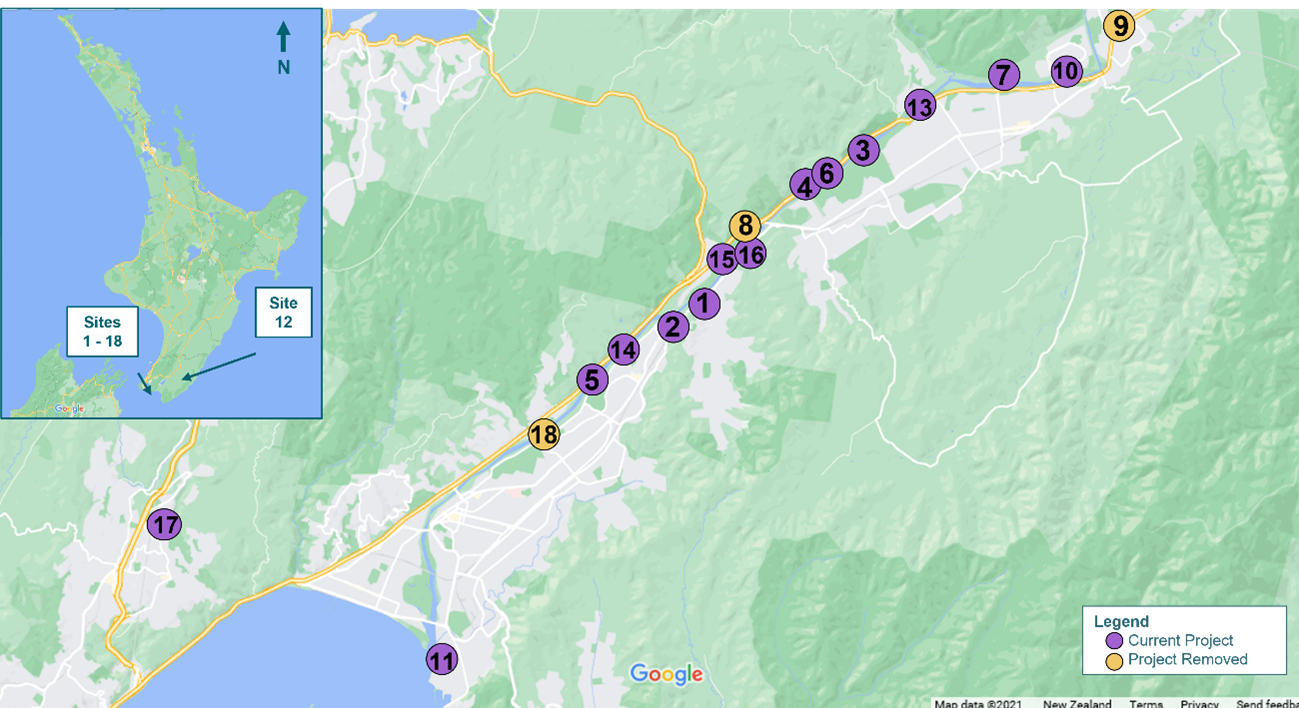

Through the Kānoa programme of work, GW has projects on Te Awa Kairangi /Hutt River, the Ruamāhanga River and the Porirua Stream. Within the projects, there are eighteen separate locations of works. The works comprise flood and erosion protection in Te Awa Kairangi/Hutt River and landfill erosion protection in the Ruamāhanga River. A further project repairing the Seton Nossiter culvert on the Porirua Stream has been added, with additional GW funding supplied for this project. Refer to Figure 2 for a location map of the projects and Table 1 for the full list of projects, which are shown on the location map.

Figure 2: GW Climate Resilience Programme Location Map

Table 1: List of projects for the GW Climate Resilience Programme

|

1 |

Lower Hutt, Stokes Valley: Erosion Protection |

|

2 |

Lower Hutt, Pomare: Bridge Stopbank Protection |

|

3 |

Upper Hutt, River Road: Erosion Protection |

|

4 |

Upper Hutt, Wellington Golf Club Right Bank: Erosion Protection |

|

5 |

Lower Hutt, Pomare Left Bank: Erosion Protection |

|

6 |

Upper Hutt, Wellington Golf Club Left Bank: Erosion Protection |

|

7 |

Upper Hutt, Tōtara Park Horse Paddock Right Bank: Erosion Protection |

|

8 |

|

|

9 |

Gemstone Drive: Erosion Protection |

|

10 |

Upper Hutt, Tōtara Park Right Bank: Erosion Protection |

|

11 |

Seaview, Port Road: Erosion Protection |

|

12 |

Masterton, Ruamāhanga River Road: Erosion Protection |

|

13 |

Upper Hutt, Poets Park: Park Enhancement |

|

14 |

Lower Hutt, Taitā Park: Park Enhancement |

|

15 |

Lower Hutt, Manor Park: Shared Pathway Construction |

|

16 |

Upper Hutt, Hulls Creek: Bridge Construction |

|

17 |

Johnsonville, Seton Nossiter: Culvert Repair |

|

18 |

|

In funding the projects, Kānoa have provided $10.8 million, and GW has put in around $10.0 million for the overall programme. Hutt City Council is contributing $80,000 (for Site 15) and Masterton District Council is funding around $300,000 for the erosion control works along the Ruamāhanga River, which will also help prevent the now-closed Nursery Road landfill from eroding into the river (Site 12). KiwiRail have also funded $90,000 for work under the Pomare Bridge (Site 2).

While engineering outcomes are readily achieved as part of business as usual for council projects, achieving social procurement outcomes has proven a greater challenge. GW has a partnership relationship with Māori in the region, and a stakeholder relationship with TAs, Department of Conservation, and Fish and Game (Fish and Game is a not-for profit organisation that manages, maintains and enhances sports fish and game birds, and their habitats, in the best long-term interests of present and future generations of anglers and hunters).

Stakeholders and Broader Outcomes

Broader outcomes, including engineering and social procurement outcomes, is a novel concept embraced by the project team. It consists of four main strands - economic, social, environmental and cultural, and seeks to connect all organisations and individuals. Persistence and reflection have been necessary on the journey to ensure meaningful relationships are formed. Whether the relationships were internal or external, with partners or stakeholders, GW had to really examine what was desired rather than imposing our assumptions around what was needed. One driver to achieve tangible broader outcomes came from the Crown, ensuring the requirement to LISTEN to what was wanted.

Throughout the course of the programme, the project team have maintained relationships with many other complex organisations, including the public, thirty-five consultants and contractors, four Crown entities, three councils, two utility providers and four mana whenua partners (mana whenua means the indigenous people (Māori) who have historic and territorial rights over the land. It refers to iwi and hapū (Māori tribal groups)).

A different way of working, and of listening, is shown in developing GW’s key relationships with mana whenua partners.

Mana Whenua Partners

The context for understanding the partnership of Regional Councils with mana whenua is Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi). The Treaty, the founding document of New Zealand, was made between representatives of the British Crown and representatives of Māori iwi and hapū. The Treaty helps the understanding of the connection between mana whenua, the land (whenua) and sea (moana) and the New Zealand Government's obligation under the Treaty Contract.

GW has a formal relationship with mana whenua. This means mana whenua have a legal status when reviewing the design and construction of the projects within GW’s work programme.

To help the project team to understand the aims of mana whenua a hui (meeting) was held with each iwi (tribe). Set-up for the meeting was important, in that it was held in a neutral space with the chairs arranged in a circle, thus recognising that each person had the same mana (prestige). Attendees then talked until all grievances were aired, allowing past issues to be raised and heard. This enabled meaningful relationships to be formed with real conversations.

However, some past grievances cannot be repaired with this approach as they hold deep and historic hurt. For example, within the Site 12 project, the team were charged with protecting a large refuse dump that was placed next to the awa (river), where the dump has the potential to be washed into the awa in a large flood event. The dump was initially created 70 years ago and was placed on the historical location of a Pā (fortified village). This was humiliating and hurtful for the local kaumatua (Māori elder) to speak about.

Through continued conversation, a misalignment of values was recognised in the context of the project, as the aims and values of the project partners were not always the same. Each project partner, GW and each of the four local iwi, had their own perspective. Focusing on collaboration, common ground was discovered among the iwi who each desired a strengthened relationship with Ara Poutama (the Department of Corrections) to support incarcerated Māori. To act on this desire, an initiative to strengthen iwi-Ara Poutama relations was incorporated into the Project Plan. While not only benefitting local iwi, this initiative also resulted in unexpected benefits for the programme, through strengthened relations and trust in GW amongst many stakeholders.

The project team is achieving its traditional goals of time, cost and quality, as well as discovering that our partners and stakeholders want to be involved with broader outcomes. GW considers this stemmed from individuals being invited to be involved in discussions and decision making, thus giving mana whenua the ability to directly contribute.

In the contracts between GW and iwi, funding is provided to the iwi for their involvement. This involvement includes co-design on design aspects such as plantings, signage, storyboards, art, knowledge exchange, involvement in communications, and developing mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) measures and indicators that can be monitored to assess any project impacts on flora and fauna.

The importance of relationship and the opportunity for all to participate in evolving discussions cannot be underestimated. This ensures a genuine partnership with mana whenua through GW’s work programme.

Social procurement

As of 2018, considering and incorporating broader outcomes is now a requirement of all government agencies in New Zealand (MBIE, 2022). With the inclusion of broader outcomes, secondary benefits result from the procurement and delivery of project work. These secondary benefits, which may include benefits to culture, economy, environment, or society, result in more holistic benefits for impacted communities. To deliver on contracted Kānoa commitments, GW has been working to fit the needs not only of stakeholders and partners, but of the community overall through its broader outcomes programme. This is the first of GW’s flood protection programs to explicitly incorporate broader outcomes. Over the course of its transformation, the programme has now come to include over fourteen different initiatives within those four main outcomes: supporting the economy, the environment, culture, and society – all aspects of our community.

In the area of wellbeing, two main initiatives support the mental and physical wellness of workers for GW’s main contractor Mills Albert Limited (MAL). MAL is a local, Māori owned business based on the Kapiti coast. MAL have been very enthusiastic about worker wellbeing and through this project GW has been able to provide the platform and targeted financial support through the projects’ broader outcomes funding for MAL to develop ideas and initiatives to support MAL’s workers in new ways. Starting discussions around mental health is an essential step towards reducing the historical stigma around the topic. With MAL now focusing on mental wellbeing, they hope to shift the culture, which is especially important given the industry they work within, as the construction sector has the highest rates of suicide across Aotearoa New Zealand.

MAL is implementing an extensive mental wellness program: they’re creating policies and procedures around mental health, hosting resiliency workshops, and providing mental health training for their workers. In a holistic approach, to support physical worker wellbeing for a workforce that’s predominantly middle-aged, Māori, and male, working with a local doctors clinic, MAL is providing an annual prostate screening program. They became aware that another contractor had recently started a similar programme, and that it had great uptake. The programme was also directly impacting the health of multiple workers – with positive test results coming back. GW, through the project’s broader outcomes, is now supporting MAL to do the same.

Apart from wellbeing, GW is also focussing on worker career development. At the beginning of the program, GW connected MAL with local iwi, Ngāti Toa. Since then, their relationship has blossomed: MAL have employed three people from the local Ngāti Toa marae: one engineer, and two spotters. To further create long-term benefits, GW is supporting workers to gain certification to progress their careers: for example, through broader outcomes funding GW is helping a female, Māori, youth worker to gain certification in her passion, which is business. Last year she was able to complete her first course in Organisations Management, and now this year, she’s going on to complete part two.

In total, through targeted broader outcomes funding as part of the climate resilience project, GW is supporting at least 15 workers to gain certifications or licensing. This licensing is facilitated through the creation of a new role, a fulltime vehicle trainer who will be providing more than 12 workers with training time in machines and vehicles that otherwise wouldn’t be possible for them. This training is enabling the workers to accelerate their vehicle licensing process so that they can progress their seniority and careers.

A third area of focus for broader outcomes is that of environmental benefit. Environmental outcomes are part of GW’s mandate. In this program, GW has approached with a different perspective: merging GW’s environmental initiatives with cultural, tangata whenua-led initiatives. (Tangata meaning people, whenua meaning land). Through hui with Ngāti Toa, collaboration between partners has resulted in a rongoā garden being included in Project 13. Rongoā is the traditional Māori healing or medicinal system. A rongoā garden is full of plants used in traditional, Māori medicinal practices. The plant selection and design has been carried out in partnership with representatives from Ngāti Toa as well as GW’s consultants. The rongoā garden will be planted in a popular community park where information panels will inform the public of the importance of rongoā, and members of the local iwi will be able to collect plants and teach their tamariki (children) for generations to come.

A further environmental project is the restoration of a wetland in the Wairarapa, at Wairarapa moana (Lake Wairarapa), which has been able to be facilitated as part of this programme and is an area of great importance to GW iwi partners in the Wairarapa.

Altogether, approximately 70,000 native plants have been procured for planting along Te Awa Kairangi/ Hutt River and the Ruamāhanga River at the majority of the sites listed in Table 1.

Community Enhancement and Involvement

Projects included as part of the programme have wider community benefits. The benefits include river-berm park enhancement, involving partial design of the river corridor environment to make it more people-friendly and include a large area of planting for CO2 mitigation. Vehicle parking areas to keep vehicles off the river berm and stopbanks have been included, as have multi-use pathways and an active transport bridge. Fish passage has also been enhanced where possible.

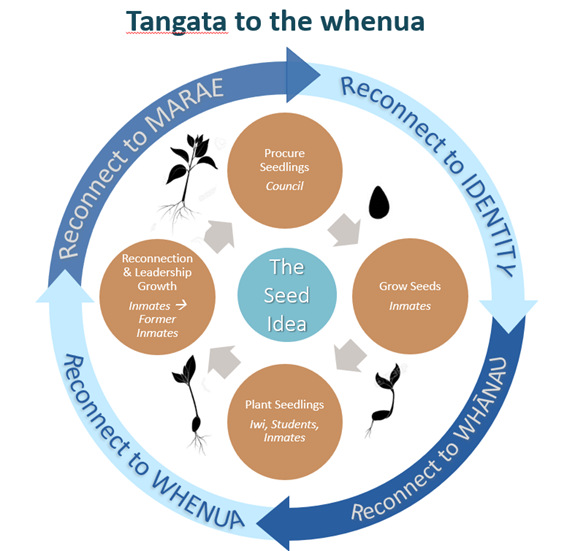

Approximately 18,700 plants have been procured from a local correctional facility: Rimutaka Prison. Procuring plants from the correctional facilities has enabled relationships to be strengthened with project partners, and also given wider social procurement outcomes through the ‘seed idea’, developed with iwi.

Figure 3 shows the ‘seed idea’ for opportunities able to be realised through reconnecting tangata to the whenua, when the tangata have become isolated from their iwi and identity. Prisons have a population of 52% Māori inmates (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2021), while the general New Zealand population is 16% Māori. The ‘seed idea’ shows how GW procuring seedlings from Rimutaka Prison allows the inmates to grow the seeds. The seeds are nurtured in the prison nursery, then planted on site by work gangs, students, the community and the work force. Inmates and former inmates are able to connect to the community, the whenua and the marae through pastoral care, and connections made through nurturing and growing seeds and plants. This idea, although in the initial stages has captured the interest of iwi and Ara Poutama, who wish to pursue it in partnership.

Figure 3: The 'Seed Idea' - Connecting Tangata to the Whenua

Programme Learnings

Kānoa considered local government business well-placed to enable social procurement, as councils are trusted enablers that connect many areas of society. However, within the project programme councils have found achieving and reporting on the social procurement outcomes to be challenging. One of the main reasons for this is that the initial social procurement targets were very ambitious. They were set in the initial stages of Covid lockdowns and response, and the context is now different. Councils, and Kānoa, are adapting targets to an institutional shift of sustainable procurement outcomes, rather than ‘targets to be met’.

GW, as part of the wider Kānoa-funded project programme, is seeking to achieve wider benefits from the programme in showing relevance of river management to the wider community. It enables demonstration of community and environmental outcomes being part of engineering solutions and presents a more persuasive case to secure future government funding for flood protection. For GW, the projects provide the Flood Protection Department a role in leading GW policy and practice in embracing social procurement as part of ‘business as usual’.

Specific challenges that have been overcome in this work programme are:

- Carrying out a large work programme within a framework set up for ‘business as usual timeframes’. For example, procurement processes within GW can take up to 16 weeks.

- Appreciating the need to create new processes, and document processes in place for the project team of new staff and consultant contractors.

- Working within resource consenting and environmental constraints that have not been tested, for example needing to apply a new operational consenting process that was not yet complete, and working on sites where fish, penguins and lizards are found, had its own construction challenges.

- Consultation around working on culturally significant sites.

- Forming good and enduring relationships with partners and stakeholders.

- Working within Covid-19 impacts on people and priorities. For example, iwi were concerned about keeping people fed and vaccinations, not responding to requests about GW projects

- Needing to engage the project team, as this programme did not involve routine project management.

- Establishing what was meant by ‘social procurement’, and putting it in place within the project team, for example, with regard to diversity.

A key lesson learnt through the creation and implementation of the department’s first broader outcomes programme is that to successfully implement broader outcomes, which is in essence, to successfully support the community, you need to listen to the needs of your community. GW’s role is to be the spark, the one who brings the encouragement, and then to let the community be the ones to lead the ideas. They’re the ones that can grow the seeds and nurture them into the future.

Through this programme, GW has been able to bring people together, forming relationships that we expect will continue on to the future, even without us – which is the aim, creating sustainable, long-term benefits which are wider than those achieved by completion of engineering projects.

References

Ara Poutama Aotearoa Department of Corrections. (March 2021). Prison facts and statistics – March 2021. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/statistics/quarterly_prison_statistics/prison_stats_march_2021#ethnicity

Greater Wellington. (March 2022). Your region. https://www.gw.govt.nz/your-region/

Greater Wellington Flood Protection Department. (July 2013). Guidelines for Floodplain Management Planning

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. (2022). Broader Outcomes. https://www.procurement.govt.nz/broader-outcomes/

Stats NZ. (2018). Wellington Region. https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/wellington-region

Stats NZ. (2020). Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2022. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2020

Te Uru Kahika Regional and Unitary Councils Aotearoa. (January 2022). Central Government Co-investment in Flood Protection Schemes: Supplementary Report.